Stalin

Stalin liked me a lot.

He used to come down and stay with us, whenever

He could snatch a few days off,

From ruling Russia.

We´d put him up in the old caravan, behind the house.

A few blankets. The odd meal now and then.

He´d never come to the door, never make a nuisance of himself.

I assumed he was just being polite.

We´d smoke a bit of weed together,

And have the most amazing raps,

Long into the night.

He was always good as gold with us.

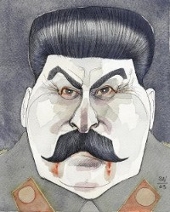

We never saw that fearsome Soviet scowl.

Or heard those dread sarcastic threats,

That made grown men shit, and shoot themselves,

Or their wives, or each other.

We only saw that twinkly, Georgian grin,

From beneath the fine, avuncular moustache.

Charming, thoughtful, witty on occasion,

And an endless flow of sparkling conversation.

He had such depth.

There was nothing he wasn´t interested in.

And, he was never any trouble.

At least not at first.

Of course, I never approved of his policies.

His persecution of the so-called ´Kulaks´.

The planned famines. The mass deportations.

The break-neck industrialisation,

With all it´s upheavals and lamentations.

The calamitous collectivisations.

The Terror. The Purges. The Gulags.

These things were all loathsome to me.

And after that terrible deal with Hitler,

With poor Molotov, his wife already under investigation.

All her friends locked up in the Lubianka, wailing.

I don´t know how I managed to stay so quiet.

He must have known, must have seen it in my face,

That I wasn´t comfortable with this.

Must have suspected that, this time,

Even I thought he´d gone too far.

But then he never was the sort of man to whom,

You just came out and said that sort of thing aloud.

It´s not as though I was the only one who thought it best,

To keep my opinions closely folded to my chest.

In those days there were millions of us.

Everyone was at it.

And anyway, he liked me.

Although I wouldn´t say we were exactly friends, he listened to me.

I liked to think that perhaps, I might do some little thing,

To ameliorate the worst of his extravagant excesses.

I think I even believed that for a while.

Though, in retrospect, I came to know it wasn´t true.

In fact, to be honest, I hated him.

Having him around was pretty nerve-wracking, really.

It was OK at night, when it was just the two of us.

We would mellow out, and we´d talk about anything and everything.

And he´d be great.

He would usually sleep in late,

After nights like that.

But then, in the day, with people to and froing,

From the house, those who understood, would be tip-toeing

On eggshells, like a mouse, worried sick that one of those who didn´t,

A child, or somebody naive, or just plain dumb,

Would say the one wrong thing,

That would bring,

The sky of wrath and ruin down upon our household.

These were tense times, truth be told.

Then there was this time he came to stay,

And he just wouldn´t go away.

Each day, he would say something like;

"I return tomorrow" or "I really must get back quite soon now".

But days ticked past, turned into weeks, and still he hadn´t gone.

I tried curtailing our late night chats, feigning tiredness,

Retiring early, hoping he would get the hint, or just lose interest.

But this just made him suspicious and resentful,

Serving to exacerbate

My own already anxious state.

Eventually, I had to accept that he was never going to leave.

And that, sooner or later, someone was bound to say that one wrong thing,

Whereupon things would surely take the very worst of turns.

It had taken me a while but, at last, I had admitted to myself,

That I was scared.

Really, really scared.

I guess, I just kind of flipped at that point.

The strain, just became, too much, as it does.

Things seemed blurred and jerky,

Like a badly filmed home movie.

I just needed to get out for a bit.

Clear my head, and try to figure out,

Just what to do about

My grim, unwelcome guest.

I walked across a field or two,

To a house of dear old friends.

Only Laura was at home.

She told me Mum and Dad were out,

And I could come in for a cup of tea,

But asked, with knowing wink, if I would keep it short,

And leave quite soon,

Because the band were coming round this afternoon.

Restlessly, I paced about, while she boiled the kettle,

Up and down their wooden floor, too wound up to settle.

I don´t know what she must have thought,

Clearly not myself, and somewhat fraught.

Then suddenly, it came to me,

Like a bullet to the back of the head,

From the thrice accursed NKVD.

Stalin was dead!

He´d died in 52 or was it 53?

Dead for years before I´d even came to be!

Slowly, my mind began to pull it all together.

If Stalin were dead, just who was it in the caravan,

Who had got me so distraught and perturbed?

And these talks, far into the night?

Just what had they been all about?

I found I could not remember.

I could not remember a thing!

We...

Hadn´t talked...

About anything.

And then with a smirched and shaky clarity, realisation dawned,

We hadn´t talked about anything,

Because Stalin hadn´t been there...

At all!

I sat to let this all sink in.

Laura bought me tea, and a couple of biscuits,

And seeing that I was deep in thought, or shock to be precise,

She left me to get on with other things.

At first, relief!

We were safe!

I was safe! The house was safe and those I loved within it.

We had all been creeping about for nothing.

Or had we? Had anyone else actually believed,

That Iosef Stalin was alive and well, in our back garden?

Or was it just me? If so, for how long?

Now embarrassment.

How could you have been such a fool

To be duped like that - again?

And Stalin? How could you have come to believe

That he, of all people, would have anything nice to say to you?

Or you to him?

The implications were appalling!

I finished my tea, thanked Laura,

And made my way, back across the fields.

Absorbed and reflective.

Reaching home, I trudged up the drive,

And checked inside the caravan. Sure enough,

It was empty. Rather dank and uninviting

To be honest. No way the sort of place

You´d find a man like Iosef Stalin,

Hanging out in his spare time.

Never in a million years.

I went indoors, hung up my coat,

Went upstairs, got into bed,

Feeling shaky and a little sick.

Like I was coming down with something,

But knowing that really I was afraid.

Afraid to broach this with the family.

Afraid that they would be afraid for me.

And then, soon after, afraid of me.

Like Kafka´s beetle, awkwardly alone,

I fell dejectedly asleep.

In the following days I talked of my delusion,

With a few special and most trusted friends.

I was surprised and discomfited to find,

That they mostly thought my story rather funny.

They advised me to enjoy the thing for what it was,

And try not to take it quite so seriously.

None of them could seem to see

How disturbing a predicament this was for me.

What if it happened again?

Which bogus historical personage might afflict me next,

Which bogus historical personage might afflict me next,

With such unquestionable conviction?

Darwin, Marx (Karl or Groucho?)

Churchill, Einstein, Chang Kai-Shek?

How long might it take for me to see,

The spiteful incongruity?

What if I never realised?

What if it´s happening all over again,

Right now?

Copyright © John Ferngrove 2009